Back to the Classics: Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings

When you think of Russian composer Peter Tchaikovsky, 1812 Overture and The Nutcracker Ballet are the two pieces that first come to mind. However, he has written less known and debatably more interesting works. One of these works is his Serenade for Strings, Op. 48. The piece was written in the autumn of 1880, just after the completion of his 1812 Overture.

Tchaikovsky was dissatisfied with his work in 1812 Overture because he believed it was too loud and exciting, which is ironic because it became his most well-known piece. However, he was very happy with the results of Serenade for Strings because of his connection to the piece. In a letter to his patron, Nadezhda von Meck, he told him that, “It is a heartfelt piece and so, I dare to think, is not lacking in real qualities”, according to Classic FM.

I encourage all of you to find a recording of the Serenade for Strings to follow along as you continue reading the piece analysis.

The first movement of this piece, “Pezzo in forma di Sonata” is in Sonatina form, which is unusual for a work in Tchaikovsky’s time. Pieces are usually written in Sonata form, which contain an introduction, exposition, which contains the primary and secondary themes of the piece, development, which shows off the skills of the conductor through a variety of key changes and intriguing melodies, a recapitulation, which restates the primary themes and ties the piece home, and finally a coda, which concludes the piece. In a Sonatina form, however, one of these sections is missing, making the form an incomplete Sonata form, and in Serenade for Strings, Tchaikovsky left out the development section. This is a curious decision to make, as there is a noble introduction, followed by an amazing exposition, then followed by a repeat of what was already heard. The listener can feel that something is missing, but Tchaikovsky manages to engage the audience nevertheless. The coda is a repeat of the introduction and makes the entirety of the movement completely symmetrical. It is believed that this movement was meant to imitate Mozart, as the Magic Flute had just been discovered at the time.

The second movement, “Valse,” is probably the most well known movement from the piece. This Waltz begins by introducing the melody with the violins, and then the melody transitions between the different instruments. Unlike the first movement, this one, along with the others, follow a much more common theme, with this section being in a ternary, or three part, form.

The third movement, “Elegia,” is a slow reflective movement. Many Elegies are found in minor keys, as they were written to lament the dead, but in this movement, Tchaikovsky chooses D Major as the tonic key, making this more reflective than sorrowful. This movement is full of eighth notes and triplets being played at the same time, which creates tension in the piece that allows it to build to several climactic points. The end of the movement mimics the beginning of the movement, but is more resolved and softer, and puts the piece to sleep with a soft D Major chord that transitions the movement to the 4th.

The fourth and final movement begins with an introduction that wakes up the movement from the soft Elegie and is then followed by a quick and spirited melody. This movement, unlike the Sonatina form of the first, follows a complete Sonata form and includes a development section that truly demonstrates Tchaikovsky composing ability. However, the most amazing part of the movement comes at the end. The piece builds to a C Major cadence that has us believe the piece is over, but instead of ending the piece, he plays the introduction from the first movement, which ties all four movements together. This melody transitions to a coda that finally resolves the tension and ends the piece.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Fossil Ridge High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Sasha Chappell, senior, is entering his first year on the Etched in Stone staff. As a new journalist, he hopes to bring different ideas to the team regarding orchestra and the vast world of classical music.

Outside of Etched in Stone, Chappell is a cellist involved with the Fossil Ridge High School...

Ainsley Lotito • Mar 1, 2018 at 6:01 pm

Mmmmmm boii I came here for some sweet sweet cello and i was not disappointed. rock on.

Kaitlyn Philavanh • Feb 17, 2018 at 7:03 pm

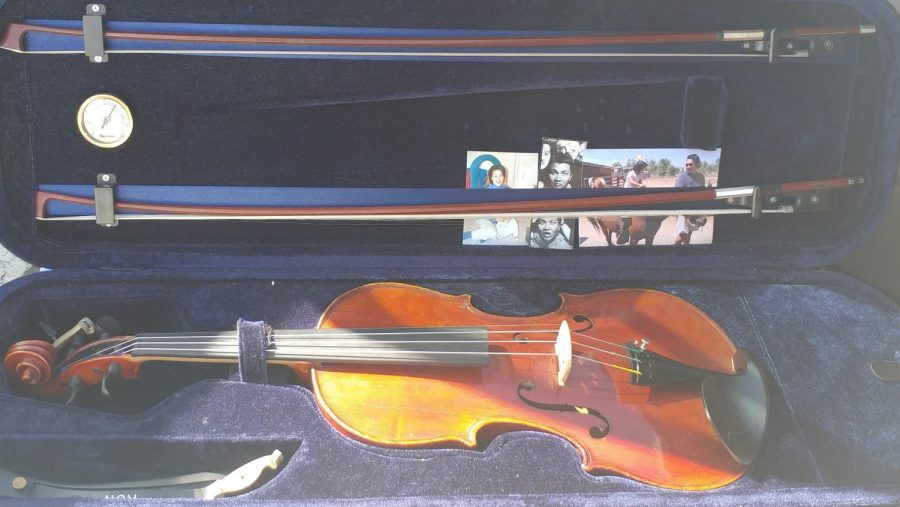

hey that’s my violin