Opinion: Cities are our best blueprint for environmental sustainability

Cities provide the best ideas when it comes to environmental sustainability.

Based on first thought, cities might seem like the least environmentally sustainable places on earth. They are known for being dirty, polluted, and filled with traffic. It seems like every movie has the classic New York City street scene, where the roads are littered with cars expressing their complaints in the form of shrill honks. Images like this can make the argument that cities are not environmentally friendly seem clear and correct.

This argument is largely dismantled when you think about cities on a deeper level, specifically on a person-to-person basis. Let us take a look at two average Americans: one lives in the city and the other lives in a suburb just outside of it.

Our city resident lives in a small apartment with their family. Their small living space equates to less energy used. Apartments with five or more units use the least amount of energy compared to other home types, and they use nearly half as much energy as a standard single family home, according to the The U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Everyday, in order to get to work, they first walk to the nearest subway station, take the train, and then walk the rest of the way to their destination. Anywhere that they could want to travel to, they can walk, bike, or take public transit. Rarely, if ever, does our city dweller need to use a car to get places, since most of their destinations are located within the city.

Our suburb resident lives in a standard single family home with their family as well. Their single family home uses more energy than the city resident. They also use more water for lawn maintenance and other things that are usually required by the HOA. According to the EPA, over eight billion gallons of water get used every day for residential outdoor water use, mainly for landscape irrigation.

In order for our suburban dweller to get to work each day, they must drive from their home to the city in their car and find parking in the city. While parking might not seem like a big deal, studies have shown that an average of 34% of city traffic is caused by people looking for parking spots. Once in the city, they can commute by transit, but if they want to go home to their family, they must take their car.

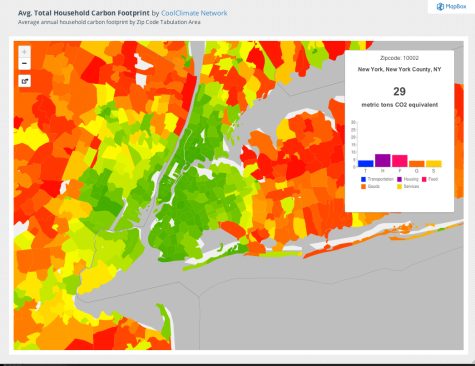

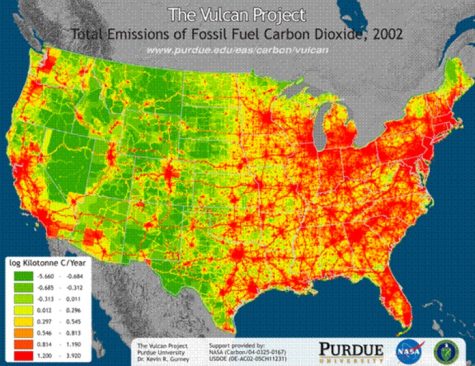

As you can see, just based on our imaginary resident scenario, those who live inside the city have a lesser environmental impact than those who live in suburbs outside of it. For a long time, the argument that cities emit more CO2 has been the main point against cities and their environmentally friendliness. That is true, and emissions from cities cause Urban Heat Island effect, which contributes to the warming of cities. But if we flip the picture around and look at CO2 emissions per person we can see clearly that people who live in the city emit less CO2 than those who live outside of it.

But why does this matter? If cities overall emit more CO2, then why does it matter that the people living inside them emit the least? The answer is simple math. Even if people living in cities do emit the least CO2 impact, there are tens of thousands of people living there. The average population in New York City per square mile is around 28,000 people. That amount of people is going to generate more CO2 than the suburbs, which have around 2,000 people per square mile.

It is also important to remember that the majority of emissions, from a city or suburb, comes from cars. Our society is overwhelmingly car centric. Highways, interstates, and stroads dominate our landscape. Most cities are far from perfect when it comes to car centrism. More and more space is being given back to cars and taken away from pedestrians.

Jeff Speck, the author of Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time, one of my favorite books, says the problem of car centrism best. “Long gone are the days when automobiles expanded possibility and choice for the majority of Americans. Now, thanks to its ever-increasing demands for space, speed, and time, the car has reshaped our landscape and lifestyles around its own needs. It is an instrument of freedom that has enslaved us.”

Car centrism is a problem that needs to be solved if we are going to continue fighting the environmental crisis. In order to fight it, we need to take a page out of the city’s books. New York City is perhaps the best model we have in America for a sustainable city, although there are, of course, things that need to be improved on. But the city has an overwhelming focus on pedestrian and public transit access, that is safe, reliable, and fast.

I myself live in a suburb just on the outskirts of Fort Collins, across Interstate 25. I have tried to reduce the amount I drive to school each day. Although I cannot bike fully to school yet — it is still too unsafe to cross I-25 over the Prospect Bridge — I have recently been driving over the bridge, parking my car, and then biking the rest of the way. Even though I have not fully converted to an emissions free commute, I have significantly reduced the amount of driving I do on a weekly basis.

Trying to integrate practices like commuting by bike and taking public transit, which are usually thought of as transport methods for city dwellers, is one of the best ways to help the environment. It is not just on your shoulders as well. We can not completely reverse the effects of suburban sprawl in our cities and towns, but local governments can expand resources like bus lines and safe bike paths across the land, rather than reserving them all for the downtown area.

No city will ever be completely environmentally sustainable. In fact, complete environmental sustainability is an almost impossible goal to reach. But we can certainly do better. Everyone can strive to do their best, whether a city dweller or a suburb dweller. While cities might be the blueprint for our environmental future, the application comes down to us.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Fossil Ridge High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Lizzy Camp is a senior and is elated to be entering her final semester as Editor in Chief, alongside Jordan Brownhill. She has spent four years working in the newsroom and has contributed many amazing articles, podcasts, and photos to Etched in Stone. She is excited to continue growing the Etched in...